A panel of residents from hotspots around the country, sharing their experiences with covid, advice for residents in areas with worsening outbreaks, and hopes for the future.

“Things started out with trepidation, then panic, then exhaustion, and now I’m just accepting them the way they are.”

The words that Dr. Kelechi Weze spoke in our panel to describe his experiences in the pandemic probably ring so true for most of us. But the sacrifices he made are beyond what many of us will be able to relate to: putting his own body and soul on the line, facing daily trauma with no way to process, losing members of his own family. As patients’ families expressed their frustration at not being able to be with their loved ones, at losing them so quickly to a virus we are only beginning to understand, at not being able to grieve, Kelechi held their grief and his own.

“We never really were able to debrief. It was just going through the day, making it through, trying to get adequate rest, and coming back,” he said.

The panel of residents discussing well-being in the coronavirus pandemic, which was put on by the Committee of Interns and Residents, a national union which represents 17,000 residents across the country, represented diverse backgrounds, experiences, and views from the frontlines of the pandemic. Residents from California, Boston, New York, DC, and Florida who have experienced different waves of this crisis and taken on leadership roles in addition to their awesome medical duties expressed frustration, fear, and hope about what they experienced, and what the future will bring.

I am thrilled to have heard them speak, and honored to be able to share their insights with you. I hope to continue to learn from these incredible physicians.

Residency is unique to the medical profession: an apprenticeship under years-long contracts that cannot be negotiated or even reviewed before signing. In the US, a marriage of academic obedience and a for-profit healthcare system can lead to some uniquely dangerous situations, especially in programs where many of the residents are international medical graduates. For them, speaking out about safety literally risks their livelihood, status in this country, and--in the case of residents from war-torn countries--their lives.

I recently gave a talk to residents and students about opioid addiction in America, and our failure as physicians to treat it. In the room, I saw young doctors struggling to stay awake, even though the room was freezing and they had done their damndest to engage. I knew that some of them had worked more than 24 hours straight, a length of time that we have incontrovertible evidence increases medical errors, car crashes, and needle sticks. Yet the medical profession has decided to sweep this evidence under the rug, to pretend it is normal and right to leave patients in the hands of exhausted physicians, and leave exhausted physicians to drive home.

I have had the unique opportunity to travel the country (in the Before Times, of course) and speak to residents, students, and practicing physicians in different kinds of distress. I have heard caregivers say they fear seeking help because of internalized shame about mental health; I have heard caregivers say they have faced retribution for seeking care; and I have heard stories of physical abuse, fraud, and sexual coercion. There is not one solution to all of these ills. A supportive program, like my residency, can be transformed in a year to be one that encourages all trainees to seek care. A place where abuse is the norm will mostly need to be survived and chipped away at the edges, until more fundamental reforms in oversight take place.

To gain entry to these bodies of oversight, I have felt pressured to soften my message. To say that residency needs only to evolve, not radically transform. The more I learn, unfortunately, the less I believe that. I do not believe that trainees should be chronically sleep deprived for years while they are trying to care for increasingly sicker patients and learning medicine at a speed that 30 years ago would have been unimaginable. I do not believe that exhausted physicians should be expected to wear and remove personal protective equipment properly in the worst pandemic in 100 years. I do not believe that we continue this system for any reason beyond inertia, convenience, and moneyed interests of the powers that be.

The consequences of this inertia will be severe for physicians in training and their patients during this pandemic and its aftermath. How many lives could be saved with adequate break times, so that we are not eating in poorly ventilated rooms within a few feet of each other? How many lives could be saved if physicians and nurses and staff were encouraged to speak about safety concerns, instead of threatened and, in some cases, fired? How many lives could be saved if we had a healthcare system that was seen as a public good instead of a money-making machine, with no incentive to shoulder the burden of this pandemic, or ability to coordinate a national response?

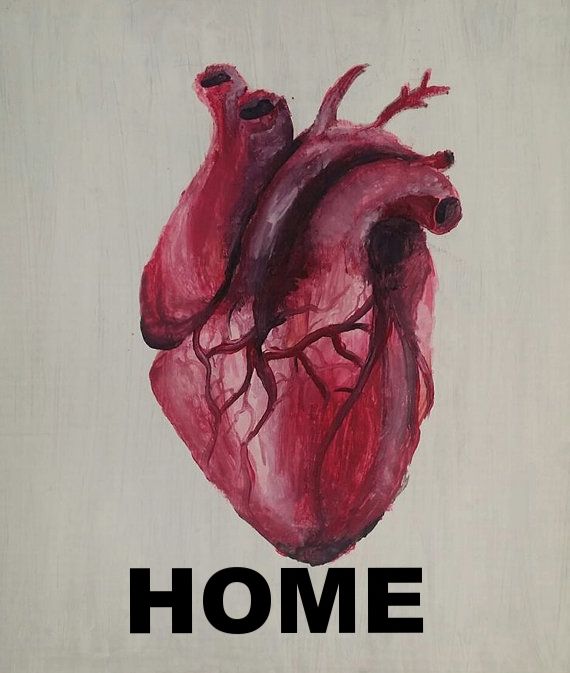

We have passed through trepidation, fear, and exhaustion. We are accepting our new normal, even as that “normal” constantly changes. Acceptance is necessary for our hearts and minds to do what we need to do, to continue to show up for our patients and each other. But acceptance should never come at the cost of hoping for something better.

We deserve something better.

Dr. Alaa Elnajarr:

Alaa is NY regional Vice President for CIR, as well a Child Adolescent Psychiatry Fellow at Montefiore Medical Center and Founder of KinectSpace. Alaa is an International Medical Graduate from Egypt, where she had her first combined neuro-psychiatry training, and is passionate about 3 interrelated subjects in teaching, wellbeing, and technology.

Dr. Kelech Wezei:

Dr Kelechi Weze is a PGY-3 Internal Medicine resident at Howard University Hospital. Kelechi is passionate about resident-led advocacy, and is one of two regional vice presidents for the DC/NJ area.

Dr. Brandon Newsome:

Dr. Brandon Newsome is a psychiatrist and physician leader out of MA with a wealth of experiences in diversity, inclusion, and wellness. He is now pursuing a Fellowship in Child Psychiatry at Çhildren's National Medical Center in DC.

Dr. Rachel Manolo:

Rachel is a pediatric cardiologist at Valley Children’s Hospital in Bakersfield, California. She recently graduated from her fellowship at Jackson Memorial Hospital/University of Miami in June 2020 where she served as the Regional Vice President for Florida for Committee of Interns and Residents

Dr. Anna Yap:

Anna Yap is a 3rd year emergency medicine resident, active in multiple resident leadership organizations on the state and national level. Currently, she serves as the Member at Large of the American Medical Association Resident and Fellows Governing Council, Southern California UC Vice President of CIR, at-Large Officer of the California Medical Association Resident and Fellow Governing Council, President of Cal-ACEP/EMRA, and is currently the resident member of the California ACEP Board of Directors and the Los Angeles County Medical Society Board of Directors.

Resources for health care professionals who are struggling:

“Project Parachute is dedicated to helping any healthcare worker find a therapist. Over 600 therapists around the country have donated their time to frontline workers who feel stressed out during this time. Connect with a therapist for telehealth in your state at https://project-parachute.org”

“The Emotional PPE Project (http://emotionalPPE.org) connects healthcare workers in need with licensed mental health professionals who can help.

No cost. No insurance. Just a trained professional to talk to.

We are a grassroots nonprofit collective of therapists, scientists, physicians, and nurses who seek to lift the multiple barriers that healthcare workers have when in need of mental health care. Any individual in a healthcare related field can contact one of the over 350 therapists in our online directory and receive no cost no insurance Emotional support.”