Getty / Karl Tapales; Design / Morgan Johnson

As a primary care provider, I meet dozens of patients every week who are considered, by BMI standards, overweight or obese. Many look to me for help. But the truth is, that’s a difficult place to be in as a doctor.

Let's consider a scenario that isn't uncommon in my practice: I'll meet a patient whose BMI is categorized as obese and who has struggled throughout her life with her weight. She's seen nutritionists, been to weight loss clinics, and tried several diet drugs and supplements. She has borderline high blood pressure but is otherwise healthy, and she's asking me what I can give her to lose weight.

There is no perfect answer to that question—and it brings up a lot of other questions for me about what my role is.

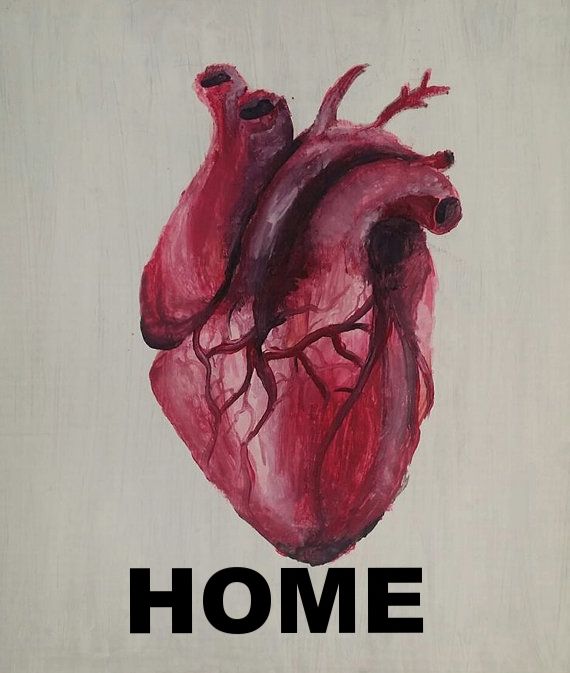

I know that, by BMI standards, this patient is at an increased risk for metabolic syndrome, and, as a result, heart disease, even though she doesn't have other risk factors. But I also know that brief weight loss counseling could leave her with the impression that I am endorsing “quick fixes,” like largely unregulated weight loss supplements, overhyped cleanses, and diets promising quick and easy weight loss.

While it’s my duty to give patients all of the information I can about ways to improve their health, I also know that suggesting weight loss can be a problematic and loaded prescription, with physical and emotional consequences.

As medical school and residency drilled into me, it’s an essential part of my job to counsel patients with BMIs in the overweight or obese range about losing weight. But this maxim ignores the reality of what we know happens when people are told “just lose some weight.” It perpetuates the misconception that weight loss is a simple matter of willpower.

Still, many medical professionals dole out the old adage of “eat less, move more,” knowing that it doesn’t end up working in most cases (not to mention the fact that it's entirely possible to be active and athletic while also having an obese BMI). One study found that fewer than one in 100 people who were obese were able to achieve a "normal" weight by BMI standards after nine years.

That’s not to say that slow, healthy weight loss done gradually is impossible. But for people who have been characterized as clinically overweight or obese for most of their lives, it often takes significant changes in almost every aspect of their lives—as well as the time and money that this would require—to lead to modest weight loss.

We also can’t gloss over the fact that obesity is often the result of many things, including genetic, biological, and environmental factors. And even patients whose overall health may improve from weight loss and who are motivated to lose weight may not have the tools to do so, especially if they lack the financial resources and/or have little control over their schedule.

Recommending weight loss in this simplistic manner can be more than frustrating to the patient; it can be dangerous.

We’re bombarded with “cures” peddled every day—whether it’s on TV, on Instagram, or even from well-meaning friends. In five minutes of counseling, I can’t undo years of miseducation or untangle health issues from deeply ingrained messages that tie weight to self-worth. Telling someone to lose weight without helping them to do it means feeding into this toxic culture.

When we fail to approach this issue thoughtfully, we can end up hurting our patients. Someone with disordered eating patterns might resort to unhealthy behaviors. Someone might turn to weight loss supplements. Someone might just opt not to go back to the doctor because they felt dismissed by their physician during the previous meeting.

I do talk to my patients who want to lose weight about how to do so healthily, but to be honest, I’m still figuring out the most effective way for me to do this on an individual basis. I first try to get an idea of all the methods my patient has already tried (if any), and then I also acknowledge how hard weight loss is to do.

Physicians should be emphasizing interventions like a healthy diet and daily exercise (because they are still important beyond weight) while also preparing patients for the fact that these changes may not lead to weight loss—and that’s OK. We must help our patients think about how they want to feed and move their bodies in ways that set themselves up for a healthy future, in a way that does not imply that weight loss is easy, or even the main goal.

We can’t let patients leave our offices with the assumption that weight loss by any means necessary is going to solve all their problems.

Weight loss is often portrayed as a magic pill for everything—easy to do and mechanical in nature; but we have the power to change this conversation. The billions of dollars people spend on “quick fixes” are as absurd as trying to cure asthma with a week in the country. We have to find a way to put weight in a context that does not imply that a certain number on the scale is the definitive marker of well-being. It’s our job to explore with patients why they want to lose the weight, and what health outcomes (both physical and mental) that would realistically bring.

Patients shouldn't have to spend so much of their lives waiting to live until they're at the "right" weight—nor should they feel like they need to put themselves at risk to get there.

Originally published in Self Magazine