Today is Father's Day, a day that for many is fraught with sadness.

Over the past week in clinic, I have heard from patients with estranged relationships with their fathers, abusive relationships, distant ones. People who have grown apart from their fathers and cannot explain why. People who have lost their fathers and who have unanswered questions. It has been easy to consider this day from a child's perspective. I don't have children of my own, and my own father is such a kind and generous man, so easily balancing unconditional love, tenderness, and steadfast consistency, that it has been hard for me to empathize with men that fail.

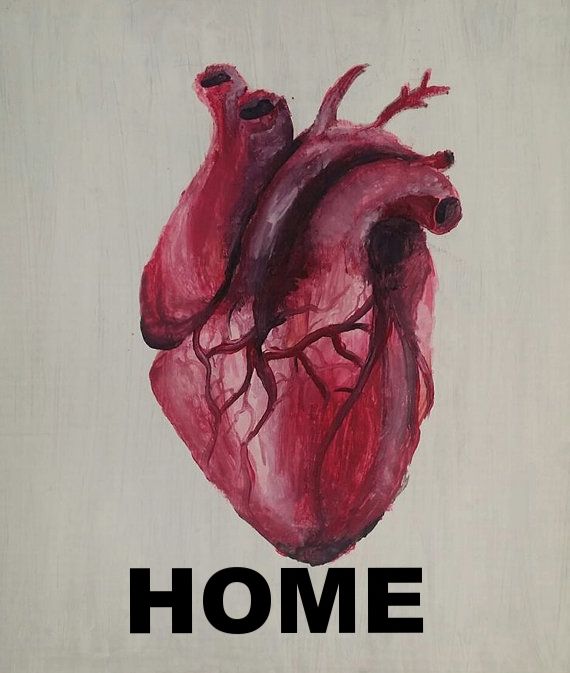

But I am lucky to have a job where my empathy is challenged every day. Failing at fatherhood is also the story of many of my patients, especially those suffering from addiction. One young man told me his kid will spend her first father's day without him as he struggles to get sober. The pain on his face almost cracked me open. Sometimes in my work I stumble on a kind of sadness I will never experience, one that pulls at the edges of my heart until my whole world opens up.

I have had fathers who have failed me: the professional fathers of medicine who were supposed to know what was right and apprentice me into their sacred trade. But they let me down. In my days as a student and resident, I was taught that opioids were a clear and easy way to treat nearly every kind of pain. My professional fathers were seduced by this promise, and did not spend enough time questioning its providence. Now my generation of doctors spends at least part of every day trying to correct this terrible mistake. It is difficult to understand how this happened, and even harder to empathize with those who made the mistake.

But I know these physicians. I know that they, like me, were trying to do the right thing for the patients that trusted them. If they were misled, I can be misled too. Understanding this means putting away childish things. It means living with the terrible knowledge that I will hurt someone, even when I think I'm doing the right thing.

Over the past few months, I have tried to understand how physicians could be responsible for the greatest public health threat of my time, and what it means for the future of medicine. I'm proud to share that reflection with you. I have received a lot of wonderful responses, but the one that meant the most to me was a note from a young woman. She told me that my article helped her process the anger she carries for the physician who started her mother on pain medication. To help someone else fill in the edges of their own story is the highest compliment I could be paid.

I hope an honest accounting of our mistakes can be a first step in moving forward. Thank you for reading.