The gap between the reality of medicine, and the way the public thinks about medicine, is growing, not shrinking.

-Malcom Gladwell, from “Malcolm Gladwell on Fixing the US Healthcare Mess”

It’s a Friday and I am about to see patients in my clinic in Everett. I have a pile of papers to get through, phone calls to return, and journal articles that will, in all probability, never be read. A specialist group has come out with more recommendations on how I should treat my patients, with almost no input from primary care physicians. More and more productivity quotas come down from on high.

More than half of my patients cry in the visit about the challenges they are facing, their difficulty with immigration or their families or the police, their frustrations that I cannot fix their medical problems. I’m grateful when one patient doesn’t show up, so I have enough time to comfort a woman sobbing so much the interpreter can’t make out any of her words, instead of shuffling her along.

And my work load is nowhere near what is expected of me, as I have been graciously given extra time in my first year. Soon, I will have only 20 minutes per patient, regardless of their complexity.

This is not just about my practice, which is doing heroic things to provide care to people who need it, and is underpaid to do so. Just like teachers in public schools, the poorer and sicker our patients, the less support we are given to take care of them.

I was speaking to a friend recently about her busy inner-city gynecology practice. She had a 20-minute visit booked with a woman who did not speak English and did not understand her own anatomy. She came with her husband. Yelling into a speaker phone with an interpreter on the other end, the gynecologist tried to explain that the woman had an endometrioma.

The doctor pulled up pictures, then realized the woman didn’t know what a uterus was.

At the end of twenty minute, the patient was supposed to decide if she wanted a surgery on an organ she didn’t know existed before that visit. She also had questions about insurance, and she and her husband had concerns about their sex life.

Afterwards, my friend had to document what happened, clicking through an electronic records system that had none of these challenges in mind when it was designed.

“I just thought, this is not possible,” she told me. “What I’m being asked to do is not possible.”

The perspectives of people doing the most vital work in our broken health care system are often lost. Residents in training are afraid to speak up. Primary care doctors simply don’t have time to advocate for their needs, and medical societies are dominated by specialists. Politicians move forward with healthcare “fixes” without consulting nurses, physician assistants, and other providers, creating problems they can’t even conceive of.

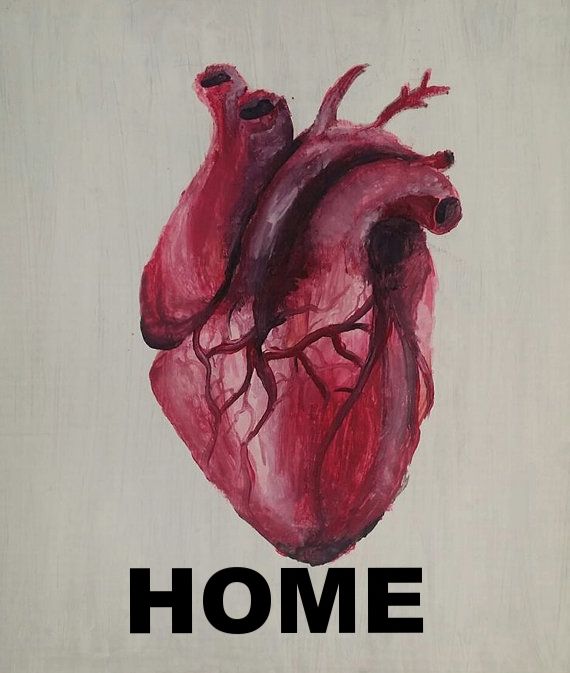

I want this site to be a place where doctors, nurses, medical assistants and patients can talk about what is happening in health care. At the heart of what is wrong in medicine is a failure of physicians to participate in the conversation about what medicine is really like.

So welcome to my site. Thank you for reading.